If the popular press is to be believed, workplaces are hotbeds of intergenerational strife, with older workers resistant to technology and younger generations insisting on recreational perks as they bounce from one short term position to another. While some of these stereotypes may be broadly true for some groups, a closer look shows that workers of different generations have adapted to the pandemic in different ways, that many of these adaptations are here to stay and that generations are balancing different work-life dynamics together. Overall, the stats show that there are fewer differences among generations in the pandemic workplace than most people assume.1

Generations and Position in Work and Life

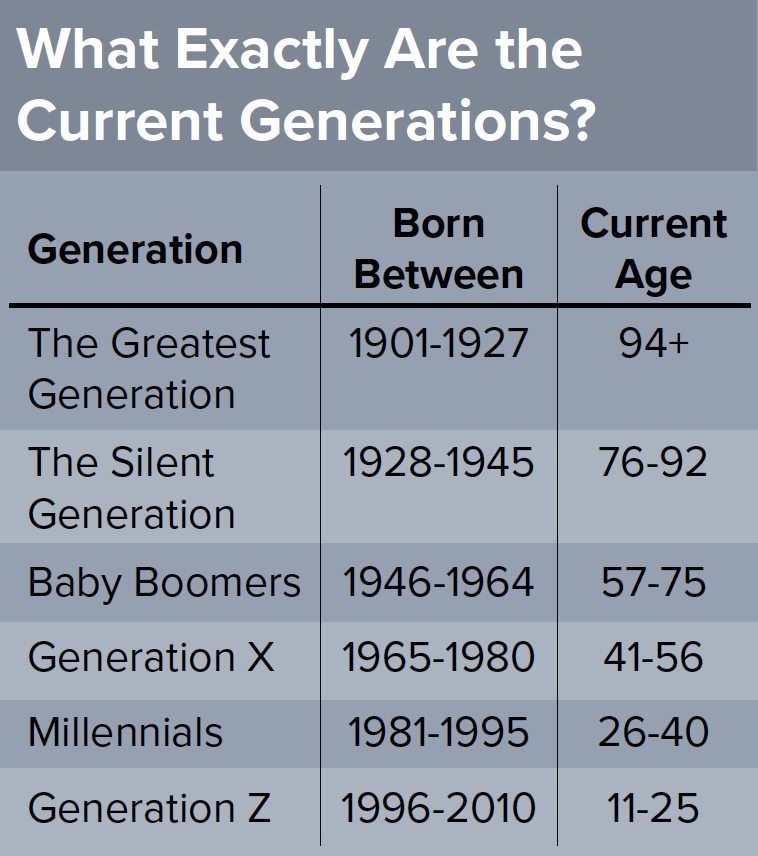

If we look at the distribution of generations in the legal profession, most of the current generations in existence are represented in the workforce.

Social scientists theorize that individuals are affected differently by key historical events at different ages/stages of life. So when we look at the effects of the pandemic on individuals of various ages, it’s worth reflecting on what responsibilities they may need to juggle.

For instance, the oldest millennials are now over 40 years old and some have even become grandparents. They represent 60% of all new family caregivers.3

And regardless of generation, attorneys may find themselves with a vast spectrum of caregiving responsibilities, from raising their own children, to raising grandchildren, to caregiving for aging parents and spouses. It should also be noted that a wide age range of individuals has “sandwiched” caregiving responsibilities, caring for both children and older parents/relatives simultaneously. For individuals with family members in nursing homes, shifting quarantines and lockdowns have made caring for their family members particularly challenging.

Nationally, one in five parents reportedly resigned or took leaves of absence in order to meet pandemic-related childcare needs.5 A recent survey reported by the American Bar Association (ABA) noted that 42% of female respondents felt they could better meet childcare responsibilities if they only worked part-time and 37% felt it would be easier to not work at all.6 The pandemic complicated already difficult childcare arrangements due to quarantines, closures and individual household risk assessments.

As the result of COVID-19 school shutdowns and quarantines, 55 million American children faced disruptions in schooling during the first year of the pandemic.7,8 While some children thrived with remote learning, the demands of remote learning created large burdens for families facing financial difficulties, families with younger children, and those who had children with learning disabilities and/or special needs.9,10,11 Accommodating children’s remote working schedule meant that many attorneys (most often women), found themselves sacrificing their own sleep to meet the demands of both work and their children’s remote learning schedules.

On the other hand, the “ABA Journal” reports that the COVID-19 pandemic has caused the vast majority of older attorneys to rethink their retirement plans, with 53% stating that the pandemic caused them to delay their planned retirement, and 47% felt impelled to accelerate their anticipated retirement date.12

The Great Tech Divide?

If you spend any time on the internet, you’ll know that one of the major generational divides is technology. For every baby boomer attorney who can’t seem to turn off their Zoom cat filter, there is a Gen Z whiz kid creating a meme within seconds. But within the practice of law, a survey done by the Association of Corporate Counsel found that there were no real differences between boomers and millennials regarding workplace adoption of new technology.13 As tempting as it may be to attribute this to novel, pandemic-related changes in legal practice, the survey data was released in January of 2020, months before COVID-19 caused disruptions in the U.S. legal landscape.

Moreover, the notion that older generations are slower or more reluctant to adapt to technology is nothing new. In 1989, 32 years ago, when home internet connections were few and far between, and most workplaces still prominently featured typewriters, the “Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal” published an interview with an attorney who was an early adopter of

The author noted that while not all attorneys will use technology to its fullest extent, it isn’t necessary for all attorneys in a firm to have the same level of technological adoption, but that all attorneys using technology need to be mindful of good security and file backup practices.14 These themes persist today. In an article published just two years ago, the same key points emerge – not all new technology needs to be used by all attorneys, but good computing practices are vital for all.15

Conclusion

Members of the OSBA's Senior Lawyers Section and friends contributed their own experiences practicing law during the pandemic. The sentiments they expressed largely align with those of lawyers across the country. Some reported earlier-than-planned retirements, but others expressed improved quality of life from reduced commutes, access to online docketing and the time savings of internet-based hearings and meetings. Attorneys who were parents of school-aged children expressed frustration with ever-changing protocols that may or may not correspond with their personal risk assessments, inconsistent experiences with remote learning and limitations on the availability of childcare. And attorneys of all ages expressed appreciation for improved remote video communication technology and increased adoption of same by family and friends.

While it may be too early to speculate on what the long-term effects of the pandemic on society will be, as a profession, we can use these first two years as an opportunity to find new and creative ways to help each other balance responsibilities, across generations, especially when we keep in mind that more connects us than divides us. The technological innovations and remote work opportunities the pandemic has generated hold the potential to allow us to create more efficient workplaces and flexible work-life balance approaches.

But while the emergence of the Omicron variant pushes the COVID-19 pandemic into its third year, we can also gather the lessons we’ve learned so far to offer our colleagues in different generations a little grace in 2022. Caregivers of children and family, who may be of any generation, face a complicated future while senior attorneys may be facing quite a different end to their careers than they originally envisioned. And we may have to say goodbye to some common stereotypes: All of us have had to adapt to new technology. Remember that, next time you find yourself reminded to unmute for the 1,000th time.

Endnotes

1 https://www.apa.org/monitor/2009/06/workplaces

2 US Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/civilian-labor-force-participation-rate.htm

3 https://www.forbes.com/sites/debgordon/2021/02/20/60-of-first-time-caregivers-are-gen-z-or-millennial-new-study-shows/?sh=f827f06720f1

4 US Census, American Community Survey 2019. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=S1002&tid=ACSST5Y2019.S1002

5 https://www.marketplace.org/2020/10/23/remote-school-online-learning-parents-quit-jobs-take-leave-of-absence/

6 https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/digital-engagement/practice-forward/practice-forward-survey.pdf

7 Garbe, A., Ogurlu, U., Logan, N., & Cook, P. (2020). COVID-19 and remote learning: Experiences of parents with children during the pandemic. American Journal of Qualitative Research, 4(3), 45-65. https://doi.org/10.29333/ajqr/8471

8 García, E., & Weiss, E. (2020). COVID-19 and student performance, equity, and U.S. education policy. Economic Policy Institute.

9 Gilman, A. (2020). Remote learning has been a disaster for many students. But some kids have thrived. https://hechingerreport.org/remote-learning-has-been-a-disaster-for-many-students-but-some-kids-have-thrived/

10 Lancker, W., & Parolin, Z. (2020). COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making. The Lancet, 5(5), E243-E244. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30084-0

11 Kamenetz, A. (2020, July 22). Parents of special education students file lawsuit over poor remote education [Radio broadcast episode]. https://www.npr.org/2020/07/22/894343514/parents-of-special-education-students-file-lawsuits-over-poor-remote-education

12 https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/covid-19-pandemic-affected-one-third-of-older-lawyers-retirement-plans-aba-report-says

13 https://www.law.com/legaltechnews/2020/02/20/millennial-or-boomer-tech-adoption-in-legal-doesnt-come-down-to-age/

14 Chantal Eldridge, Computer Use by One Practitioner: An Interview with Robin Meadow, 5 Santa Clara High Tech. L.J. 13 (1989). https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/chtlj/vol5/iss1/3/

15 https://www.infolaw.co.uk/newsletter/2019/07/key-skills-modern-lawyers/